Variations on this legend were popularised in the Medieval period following the Crusades which sought to reconquer Jerusalem from its Muslim rule.

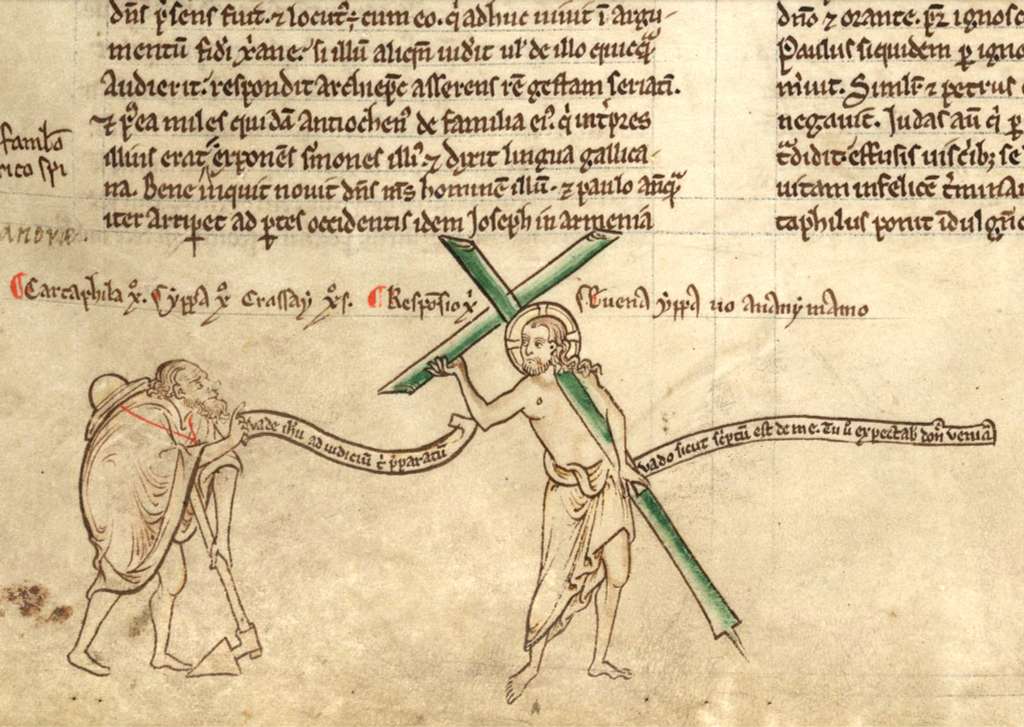

Historical chronicles evidenced ‘sightings’ of the mythical Wandering Jew, travelling from key sites for the Crusades such as Armenia, blurring the line between fact and fiction. Although the first written account is found in the 13th century—Matthew Paris’ Chronica Majora—the Wandering Jew’s dual punishments, of wandering and immortality, are shaped by biblical sources. In Genesis, after killing his brother Abel, Cain is declared to be “a fugitive and vagabond … the Lord set a mark upon him, lest any finding him should kill him”.

Influences for the Wandering Jew are also found in the New Testament. The servant Malchus is punished for his attempted arrest of Jesus. In the Gospel of John, Peter asks how the ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved will die’, and Jesus replies: “If I will that he tarry till I come, what is that to thee?” indicating at the theme of immortal waiting until the Second Coming. The first recognisable physical depiction of the Wandering Jew is found in the 1602 A Brief Description and Narration Regarding a Jew Named Ahasuerus, a German pamphlet in which ‘Ahasuerus’ is very tall, barefoot, and wears a long cloak. In later texts, he is also described as being an old man with a white beard.

What is in a name? Different names given to the legend relate to the dual elements of his punishment: the Wandering Jew refers to his itinerant travels, whilst the Eternal Jew (in German, Der ewige Jude, and in French, Le Juif errant) focuses on his inability to die. Sometimes ‘Ahasverus’ or ‘Ahasver’ is used, the name of the Persian King who supported his Jewish wife, Queen Esther, in fighting against a plot to annihilate the Jews. This is commemorated in the Jewish festival of Purim through costume and celebration, connecting with the theme of the legend of the Wandering Jew as a figure of resilience in the face of persecution.