After centuries of depictions of the Wandering Jew by non-Jewish artists and writers, the Yiddish cultural revival at the turn of the twentieth century began to reimagine the legend. Known as Der eybiker yid, this ‘Eternal Jew’ became associated with notions of resilience and empowerment, reframing the Christian legend.

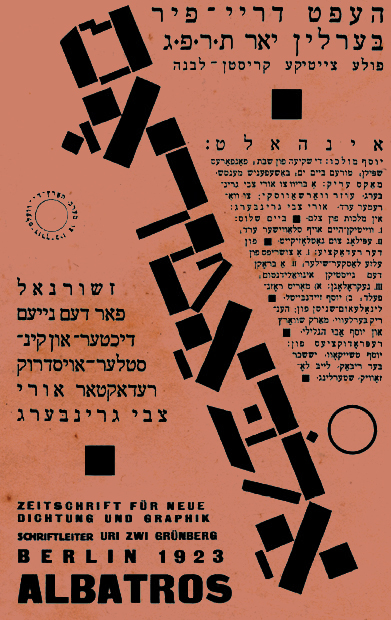

Uri Zvi Greenberg (1896-1981, Ukraine) invokes the Wandering Jew’s relationship to the Christian messianic belief that he will wander the earth until the Second Coming of Jesus. Using Jewish historical narratives, he depicts the Second Temple period and Bar Kochba revolt as the setting of the Wandering Jew for ‘In the Kingdom of the Cross’ (1923) and the Hebrew poem ‘An Oracle to Europe’ (1926).

“Wandering is your fate!

Crossing winds

After steel ships.”

Esther Shumiatcher-Hirschbein

‘The Albatross’ (translation Rachel Seelig)

‘The Albatross’ (1922) by Esther Shumiatcher- Hirschbein (1896-1985, Belarus) refers to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834, England) and the punishment of Cain. This poem presents exile as embedded in Jewish experience, rather than of immortal wandering as punishment, calling out: “Wandering is your fate! Crossing winds / After steel ships.”

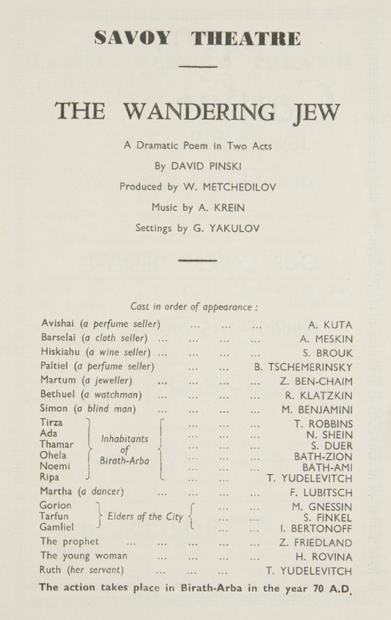

The Wandering Jew was particularly popular on the Yiddish stage, with audiences finding resonance in a figure representing the longevity of Jewish culture, history, and identity. Productions included Ezra, der eybiker yid (c. 1880s) by Joseph Lateiner (1853- 1935, Romania) and Vechny strannik (The Eternal Wanderer, 1913) by Osip Dymov (1878-1959, Poland). In Der eybiker yid (1906), Dovid Pinski (1872-1959, Bela) depicts the Wandering Jew on a neverending quest to find the child – understood to be the Messiah – who was born in the same hour as the destruction of the Second Temple. This play was translated into Hebrew by the Habima Troupe (now the National Theatre of Israel) who performed it across the globe, including a four-week residency in London’s Savoy Theatre in 1937.