In the twenty-first century, the Wandering Jew attracts the attention of writers and artists in new ways. Some have responded to the traditional masculine nature of the legend, while others have used it to understand the role of Israel in the narrative of the Second Coming.

Eternal Life (2018) by Dara Horn (1977-, United States of America) presents the character of the Wandering Jewess. Rachel willingly makes a trade to save her dying son, agreeing to become immortal. Accompanied by a fellow wanderer and her lover, Elazar, she travels from Second Temple Jerusalem to contemporary New York in a cycle of witnessing and preserving Jewish cultural memory.

Eshkol Nevo (1971-, Israel) explores the multigenerational memory and trauma of an Israeli family in Neuland (2011). The protagonist, Dori, is on a search for her father in Argentina when she meets Jamili, a Wandering Jew, in Neuland, an alternative Zionist commune. Subverting the traditional ‘historical chronicle’ narrative, Jamili recalls positive memories and encounters with figures such as Herzl and Galileo, portraying diaspora as a source for creativity, not a curse.

In Melmoth (2018), Sarah Perry (1979-, England) revives the legend’s gothic elements. The Wandering Jew becomes a woman called Melmoth, referring to the novel of the same name by Charles Maturin (1780-1824, Ireland). She haunts the guilty and collects their testimonies: in the fictitious Hoffman Document, a character recalls how he betrayed his Jewish friends to the Nazis in wartime Prague. Their fate is confirmed when the protagonist comes across a ‘stumbling stone’, brass plates that mark where Holocaust victims lived. Whilst the Wandering Jew is only a legend, these Stolpersteine act as witnesses to history, immortalising memory.

The anthropologist Edmund Leach suggests that boundaries offer unique opportunities and scope for creative thought, representing critical moments of insight. The Wandering Jew of Europe has crossed countless boundaries in his centuries of exile and has become well acquainted with them.

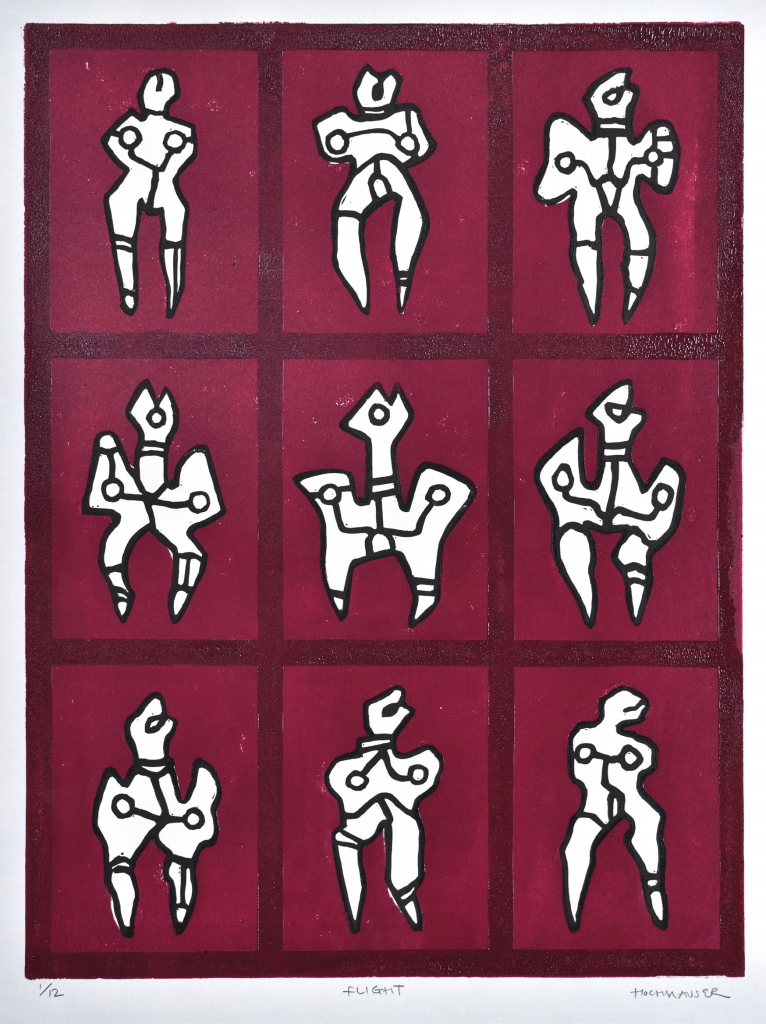

In David Hochhauser’s ‘Flight’ the Wandering Jew is peripatetic, like a bird, and it is at the climax that his wings and his eyes open to look down on the landscape below. After a fleeting look at some novel insight into the cultural scenery that denies him space, he looks on for his next branch upon which to perch.