In addition to simply ‘touring’ the travelling exhibition, sometimes giving talks or lectures specific to the venue and its audience (for example respectively for the Council of Christians and Jews, the German Historical Institute, Holocaust Centre North, or the BIAJS Conference on ‘Border Crossing’), I have also experimented with leading collage workshops. The first of these was hosted at Limmud Festival in 2024, with a group of participants already self-selected – they had chosen to come to the event, and then to my session, bringing with an expected set of knowledge and understanding about Jewishness, art, antisemitism, some creative practice. This workshop was brief but productive, demonstrating the success of the collage approach and the rich potential to be gleaned by extracting – and then re-making – the imagery and text related to the Wandering Jew as displayed in my exhibition.

Why collage?

Collage, from the French coller ‘to glue’, was formalised as a modernist art technique in the early twentieth century, creating new work by assembling together different forms. Similarly, found poetry involves cutting out, marking or covering (in the form of blackout) existing words. This literary version of collage was developed within the anti-art Dadaist movement that arose in response to the First World War, and still resonates today in contemporary methods especially for non-establishment, political and artistic practice, including for artists from Jewish or other structurally marginalised backgrounds. This application is inherently radical particularly as used in response to antisemitic tropes accusing Jews of producing unoriginal art (see Richard Wagner’s Judaism in Music) or the Nazi Degenerate Art exhibition which featured examples of modern paintings and sculptures including collages and mixed media, as in the work of Kurt Schwitters.

Arts and Humanities Festival

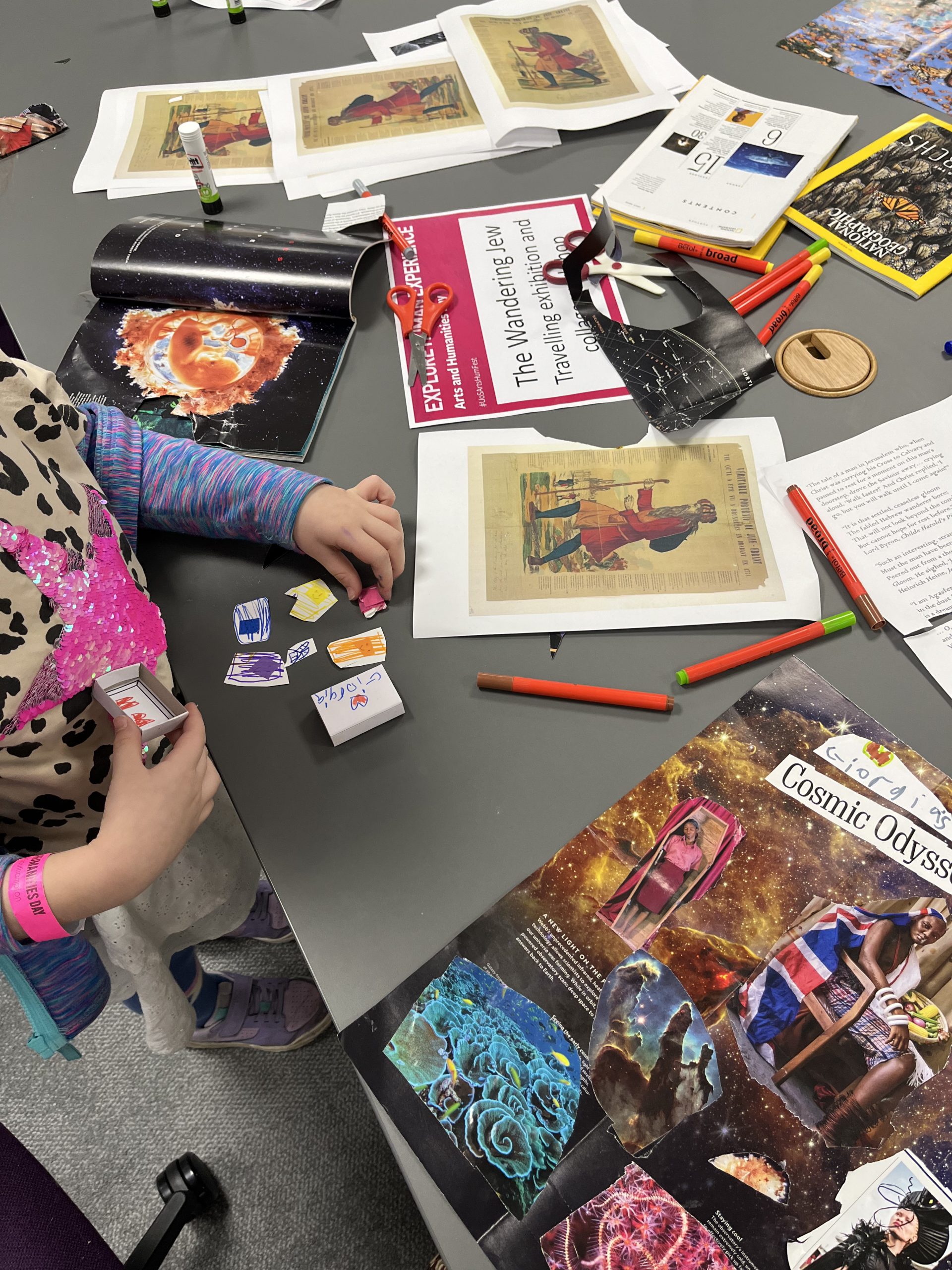

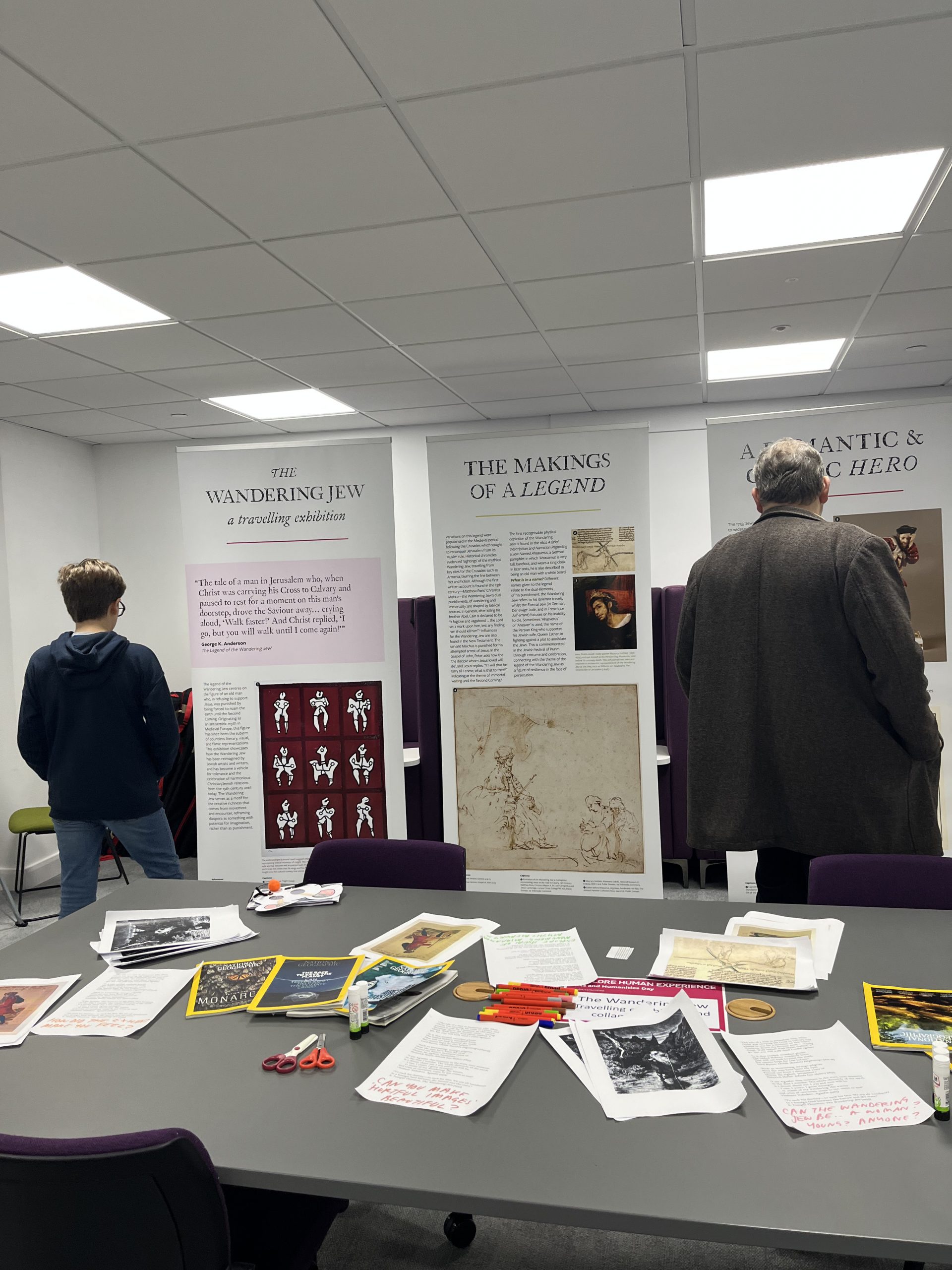

Almost a year to the day since the launch of the travelling exhibition, I was asked to bring it and a relevant activity to the Southampton Arts and Humanities Festival. This was more of a challenge – but an exciting one – as the event attracted hundreds members of the public from across Southampton and Winchester, largely families with young children looking for free weekend activities. The Arts and Humanities Festival was set up to demonstrate how academic research can be presented to wider audiences, showcasing exciting projects, outputs and findings from across the University.

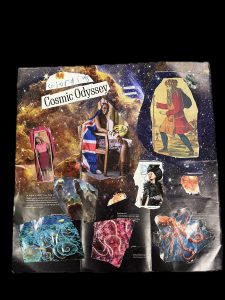

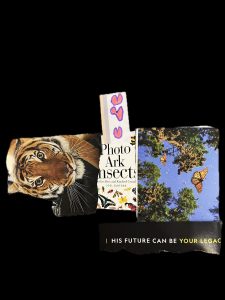

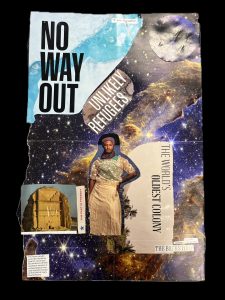

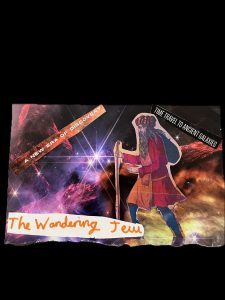

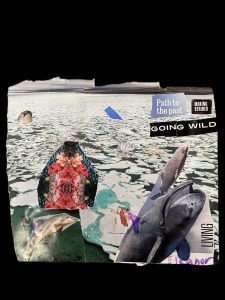

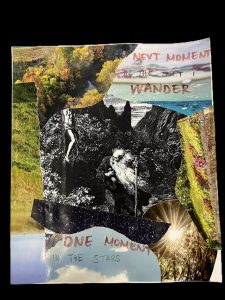

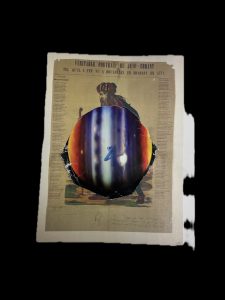

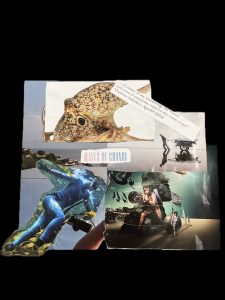

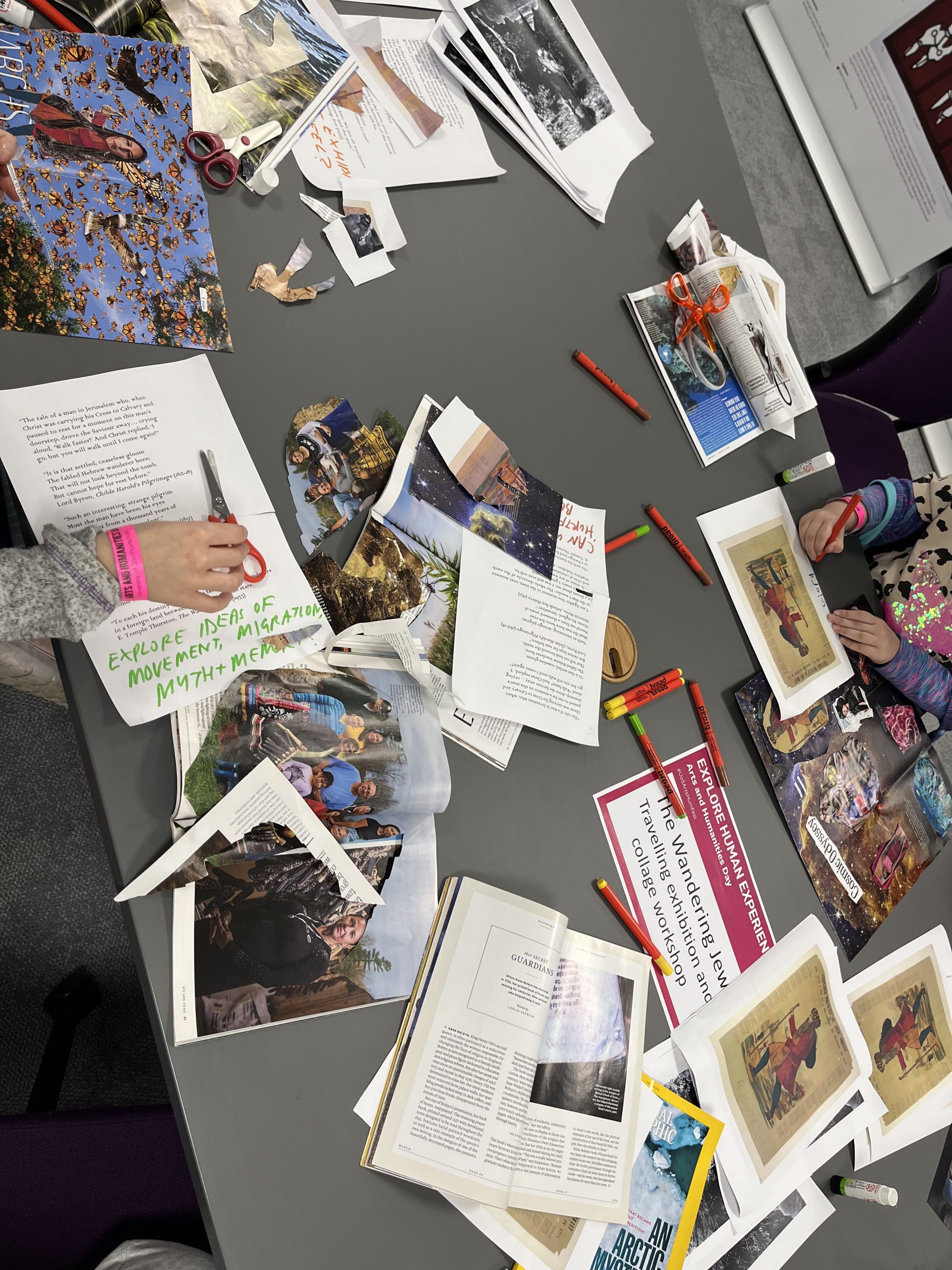

Alongside displaying the exhibition, which attracted the attention of interested young adults and parents, I reformatted the collage workshop for children. Naturally, I had to accept that the historical reality of the legend (a product of Christian antisemitism), the breadth and depth of its myriad representations across literature and art, and the intricacies of reclamation and reappropriation, were unlikely to translate well to such a young audience. Instead, I attempted to distil what the Wandering Jew represented and identify elements that could be made familiar – framing the character as a mysterious mythic creature, a historic legend, and a time-traveller (much like Doctor Who) who journeys across the earth over hundreds of years. I included prompts such as ‘How does the legend make you think about movement and memory?’, ‘Does the Wandering Jew have to be an old man, or can he be young, or a woman?’, ‘Where will he journey next – into outer space, or under the sea?’, ‘How does he connect to nature and animals?’ These were complemented by a selection of National Geographic magazines which participants were encouraged to scour and cut up to find inspiring backgrounds – of galaxies, icebergs, deep-sea coral reefs – alongside titles and captions easily applied to the Wandering Jew and his ancient travels.

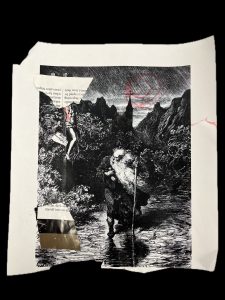

Whilst this activity did not focus on Jewishness or the history of weaponised exclusion, I found it nevertheless elucidated something of the essence of the legend: that movement can be viewed through an imaginative lens, and that historic imagery and text is not ‘out of bounds’. This connected to an earlier avenue of inquiry, reflecting on whether the colloquial invocation of the Wandering Jew without knowledge of the legend’s troubled history could still count as reappropriation? Is it possible to feel empowered reclaiming something without even realising? Similarly, if the collages produced by these children can ultimately be read as radical re-writing or re-drawing of the Wandering Jew – framing his cursed exile as creative exploring – does it matter the extent to which they were aware of this during the process of making? Each collage – which began with a discussion, looking for the first seed of idea, and then searching for images along that theme – challenged existing assumptions or expectations of the legend. Does the Wandering Jew have to be alone, or can he get married? Can he only travel on foot, or can he swim or even fly? Is he human, or is his cursed wandering a kind of supernatural magical power?

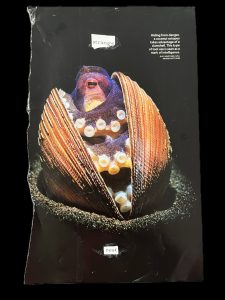

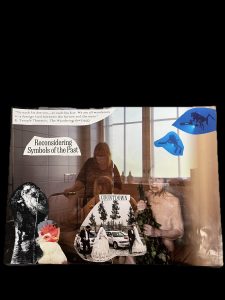

Although the exhibition itself acted as backdrop to the workshop, being surrounded by its imagery and text still offered inspiration. One young participant produced a ‘snake of doom’, a threatening underwater creature, which his father noted rhymed and chimed with that ‘settled, ceaseless gloom’ from Byron’s poem. Another participant, eager to find images of whales, reminded me of the reference to the Bering Strait in Eugene Sue’s Le Juif Errant (across which the Wandering Jew is separated from his sister Herodias) which then became the setting for the collage complete with a background of an icy surface with broken cracks down the middle of the page. Some participants also addressed the temporal nature of the legend, speaking to the curse of immortality suffered by the Wandering Jew. One collage, featuring butterflies and a lion, bore the text ‘His future can be your legacy’, another depicted the Wandering Jew’s ‘time travel to ancient galaxies’, and a third centred a tagline ‘Reconsidering Symbols of the Past’. Additionally, some of the collages literally erased part of Jesus’ body when he appears on the crucifixion alongside the Wandering Jew: in one example his head is covered over with images of trees, in another, red crayon is used over his body and a torn piece of paper with text pasted over his head and arms. These instances reflect the violent potential of cutting up imagery, yet do so in the form of embodied resistance. Overall, the affective idea of reclamation – of making hateful imagery beautiful, of employing methods of ‘cut-up’ poetry to text – was clear to many of the adult attendees. Some were inspired to share their own overlapping family histories of migration, ask about relevance to contemporary political challenges, or inquire further about the evolution of the legend in more detail.

The Arts and Humanities Day showcased successfully how the Wandering Jew travelling exhibition and collage workshop can be translated for public audiences of all ages, drawing out insights and creative reflection around universal themes whilst still grounded in the particular history of the legend and its legacy today.